The Uganda Martyrs

Their Countercultural Witness Still Speaks Today

By: Bob French

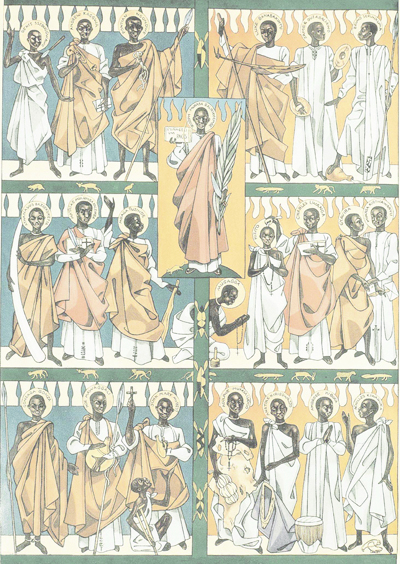

In his living room wall, Matthew Segaali has a painting of twenty-two young men and boys in Ugandan tribal dress. Some of them are standing in front of a backdrop of upraised spears; the rest, in front of flames as tall as they are.

While it appears that they are about to be put to death, the expressions on their faces are of peace, trust, and even joy. One of them is holding a palm branch; others have their hands folded in prayer; and others are clasping a cross or a rosary.

They are the men and boys whose martyrdom in 1886 is considered the spark that ignited the flame of Christianity in modern Africa. Canonized in 1964, the Uganda Martyrs are revered for their faith, their courage, and their countercultural witness to Christ.

These saints are highly honored in the Segaali home. Matthew's son Joseph is named after one of them. The whole family regularly prays litanies for their intercession in their native language of Ugandan. Their prayers have been answered so often that Matthew has lost count. "I would not be who I am without the Uganda Martyrs," he says proudly.

You may be surprised to learn that the Segaalis don't actually live in Uganda. As residents of Boston, Massachusetts, they are among the many African expatriates around the world who feel a close connection to the martyrs.

Why are these men so important to the Segaalis and to Africans all over the world? Perhaps because, as Pope John Paul II pointed out during his visit to their shrine, their sacrifice was the seed that "helped to draw Uganda and all of Africa to Christ." Despite the martyrs' youth—most were in their teens and twenties—they are truly "founding fathers" of the modern African church, which displays so much vigor today.

Planting the Seed. Their story begins with the Protestant missionaries who began arriving in Buganda (now Uganda) in 1877. Mutesa—the king, or Kabaka—welcomed them and seemed open to Christianity, perhaps because it had points of contact with his people's belief in the afterlife and in a creator god. He even allowed it to be taught at his court.

When the Catholic White Fathers (now the Missionaries of Africa) arrived in 1879, Mutesa welcomed them as well. However, he also flirted with Islam, which Arab traders had introduced into Buganda decades before, and began favoring now one religious group and then another, mainly for political gain.

The king's shifting favor created an uncertain, often dangerous climate for Christians, but White Father Simeon Lourdel and his companions took advantage of every opportunity Mutesa gave. They founded missions where they could teach people about the faith, and about medicine and agriculture as well.

In the Fathers' Footsteps. Unlike some missionaries of the day, the White Fathers took their time preparing people for baptism. They wanted their new converts to understand what it means to enter into new life with Jesus and to follow him.

Many Bugandans were hungry for their teaching and responded eagerly to this approach. "They were offered the living word of God, not just the historical facts of salvation," says Caroli Lwanga Mpoza, a historian from Uganda. "They grabbed onto it, and it changed them."

The depth of their faith became obvious during a three-year period when Mutesa's hostility forced the White Fathers out of the country. The priests returned from exile after Mutesa's death in 1884 and were pleased to find that their converts had taken it upon themselves to bring their families and friends to the Lord. Many had renounced polygamy and slavery and were devoting their energies to serving and caring for the needy around them.

Hero of the Faith. One exceptionally active convert was Joseph Mukasa, who served as personal attendant for both Mutesa and the new king, his son Mwanga. He had brought Christ to many of the five hundred young men and boys who worked as court pages, and they relied on his leadership and his clear grasp of the faith.

Mukasa had the king's respect, too, for he had once killed a poisonous snake with his bare hands as it was about to strike his master. But King Mwanga was even more unstable than his father. He was soon affected by the poisonous lies of jealous advisors, who called Mukasa disloyal for his allegiance to another king, the "God of the Christians."

Their accusations were reinforced when Mukasa reprimanded King Mwanga for trying to have the newly arrived Anglican bishop put to death. Furious that anyone would dare to oppose him, the Kabaka went ahead with the assassination.

Mukasa could have played it safe and chosen not to cross the king again. Instead, he enraged Mwanga even more by repeatedly opposing his attempts to use the younger pages as his sex partners. Mukasa not only taught the boys to resist but made sure they stayed out of Mwanga's reach.

The Kabaka finally decided to make Mukasa an example, ordering him to be burned alive as a conspirator. But here, too, Mukasa proved the stronger and braver. He assured his executioner that "a Christian who gives his life for God has no reason to fear death. . . . Tell Mwanga," he also said, "that he has condemned me unjustly, but I forgive him with all my heart." The executioner was so impressed with Mukasa that he beheaded him swiftly before tying him to the stake and burning his body.

A Terrible Vengeance. Now on a rampage, King Mwanga threatened to have all his Christian pages killed unless they renounced their faith. This failed to intimidate them, however, for Mukasa's example had inspired them. Even the catechumens among them followed Mukasa's bravery by asking to be baptized before they died.

Among them was Charles Lwanga, who took over both Mukasa's position as head of the pages and his role of spiritual leader. Like Mukasa, Lwanga professed loyalty to the king but fell into disfavor for protecting the boys and holding onto his faith.

King Mwanga's simmering rage boiled over one evening, when he returned from a hunting trip and learned that a page named Denis Ssebuggwawo had been teaching the catechism to a younger boy, Mwanga's favorite. The king gave Denis a brutal beating and handed him to the executioners, who hacked him to pieces.

The following day, Mwanga gathered all the pages in front of his residence. "Let all those who do not pray stay here by my side," he shouted. "Those who pray" he commanded to stand before a fence on his left. Charles Lwanga led the way, followed by the other Christian pages, Catholic and Anglican. The youngest, Kizito, was only fourteen.

The king's vengeance was terrible: He sentenced the group to be burnt alive at Namugongo, a village twenty miles away.

No Cause for Sadness. The prisoners were strikingly peaceful and joyful in the face of this verdict. Fr. Lourdel, who tried to save them, reported that afterwards, "they were tied so closely that they could scarcely walk, and I saw little Kizito laughing merrily at this, as though it were a game." Another page asked the priest, "Mapera [Father], why be sad? What I suffer now is little compared with the eternal happiness you have taught me to look forward to!"

The prisoners suffered greatly during the long march to the execution site, but they prayed aloud and recited the catechism all along the way. Three of them were speared to death before reaching the village. The others were led out to a massive funeral pyre. It was Ascension Thursday morning.

Eyewitnesses said that the martyrs were lighthearted, cheering and encouraging one another as the executioners sent up menacing chants. Each of the pages was wrapped in reeds and placed on the giant bonfire, which soon became an inferno.

"Call on your God, and see if he can save you," called one executioner. "Poor madman," replied Lwanga. "You are burning me, but it is as if you are pouring water over my body."

The other prisoners were equally calm. From the raging flames, only their prayers and songs could be heard, growing fainter and fainter. Those who witnessed the fire said they had never seen men die that way.

But the martyrs at Namugongo were not Mwanga's only victims. Dozens more Christians were killed in the surrounding countryside, and some of those who had taught the faith were singled out for special retribution.

Andrew Kaggwa, a friend of the king's, was beheaded. Impatient to meet his fate, he said to his executioner, "Why don't you carry out your orders? I'm afraid delay will get you into serious trouble." Noe Mawaggali was speared, then attacked by wild dogs. Matthias Kalemba was dismembered and pieces of his flesh roasted before his eyes. Before he died, he said, "Surely Katonda [God] will deliver me, but you will not see how he does it. He will take my soul and leave you my body."

Against the Grain. The martyrs of Uganda were young, but they were not seduced by the values of the royal court. They took a stand for God's law, even when it meant defying the king himself. Out of allegiance to a higher king and a nobler law, they rejected the earthly security that could have been theirs had they given in to the king's lusts.

Their example is extremely important today, Caroli Mpoza points out. It shows how faith can become a "rudder" that sustains us in times of trial and temptation. It also shows how critical it is to instill godliness in our children. If they learn to honor God and put him first, he says, they too will stand firm against the seductive values of our culture.

Like the parable of the sower, the story of the Uganda Martyrs invites us to examine our commitment to the Lord. Here are young people whose whole life of faith was marked by simple, luminous, joyful trust in God—even in the face of a gruesome death. They were "rich soil" indeed—not just for Africa, but for the whole church.

Bob French lives in Alexandria, Virginia. This story was based mainly on J.F Faupel's African Holocaust and Caroli Lwanga Mpoza's Heroes of African Origin Are Our Ancestors in the Faith, as well as personal interviews.

Comments